Paper trips, literary epics

Mauritanian Berber, Chinguetti Oasis.

Strolling through the pages

“The world is a book, and those who do not travel only read one page”, wrote Saint Augustine. Victor Hugo, in Things seen, was even more direct: “Reading is travelling, to travel is to read.” Literature and travel have always had a very special bond. Many are those who open a book to free their minds to fly away to a place elsewhere, to let themselves be transported by the words as one might undertake a journey. The book is the promise of a kind of static wandering. Homer’s The Odyssey is both a founding text of ancient Greek culture, and an astonishing travelogue. And when Voltaire wants to confront his Candid with the reality of the world during a philosophical tale, he naturally chooses to take his hero on a journey. Open a book… and let yourself be carried away.

Travel writers

Journeys of initiation, journeys experienced as an allegory of existence, the desire to confront the vastness of the world and keep a diary of it… many writers have packed their bags with additional agendas in mind. On the road, by Jack Kerouac, is the model cult novel of the Beat Generation, the artistic and literary movement. It is a stroll through the great American spaces and much more, a journey to find oneself. “We think we’re going on a trip, but soon it’s the trip that makes or breaks you”, wrote Nicolas Bouvier, one of the most famous of these travel writers in The Way of the World. Paul Theroux on the train to Asia, Bruce Chatwin in the Australian bush, Sylvain Tesson on the shores of Lake Baikal… There are those who flee and those who want to get lost, those who want to confront the unknown and those who yearn to come face to face with themselves. Some are moved by the spirit of adventure, or the quest for meaning. All share an infinite curiosity.

Sylvain Tesson during his trip to the shores of Lake Baikal.

The Gobi desert which Paul Theroux crossed by train and which inspired Riding the Iron Rooster: By Train through China (1989).

Robert Louis Stevenson travelled throughout the Cevennes on the back of a donkey, telling the story in Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes (1879).

Book in hand

Literary journeys are not only the prerogative of writers, however. Without being tempted by writing themselves, many travellers decide to follow in the footsteps of an author or a story. Some books contribute so much to the imagination of a place that they become inseparable from it. Readers pack their suitcases to discover Iceland, following in the footsteps of detective fiction author Arnaldur Indridason, or the Aran Islands of the writing of Nicolas Bouvier. Because these works add an extra dimension to their journey, many are those who slip into their bags the texts of JMG le Clézio before fl ying off to Mauritius, or of Marcel Pagnol when en route to Provence or a copy of Meharees by Théodore Monod to read under the stars, during a trek through the Sahara.

Travelling first leaves you speechless, then turns you into a storyteller

Travel companions

Almost like a true travel companion, the book becomes a participant in the adventure. Some also choose to share their journey accompanied by an animal companion: a donkey, a dog, a horse... In 2021, in Notre vagabonde liberté (Our Wandering Freedom), Gaspard Koenig recounted his 2,500km journey between Bordeaux and Rome, following in the footsteps of Montaigne, with his mare Destinada. Years before, John Steinbeck had written his Travels with Charley (1960), an account of a quintessential American journey in a motor home, accompanied by his poodle. Robert Louis Stevenson crossed the Cévennes in 1878 with his donkey, Modestine. But whomever these fellow travellers in literature might be, the goal of the journey is oft en oneself. “To travel is to discover the other. And the first stranger to be discovered is yourself”, underscores the photographer-traveller Olivier Föllmi.

The eternal return

Inevitably, the time comes when we reach the last page of the book. And the return home. Travel and literature also share this common point: they are parentheses, albeit fertile ones, that open our eyes to our surroundings, helping us to get to know each other better, and discovering other ways of living, thinking, even other kinds of realities. And of course, in turn, to recount those tales once more: “Travelling first leaves you speechless, then turns you into a storyteller”, as the explorer Ibn Battûta once said.

Sylvain Tesson on the shores of Lake Baikal, as told in the book Dans les forêts de Sibérie, autobiographical account released in 2011.

Chinguetti Oasis in Mauritania. Mauritania and its desert inspired Théodore Monod to write Méharées (1989).

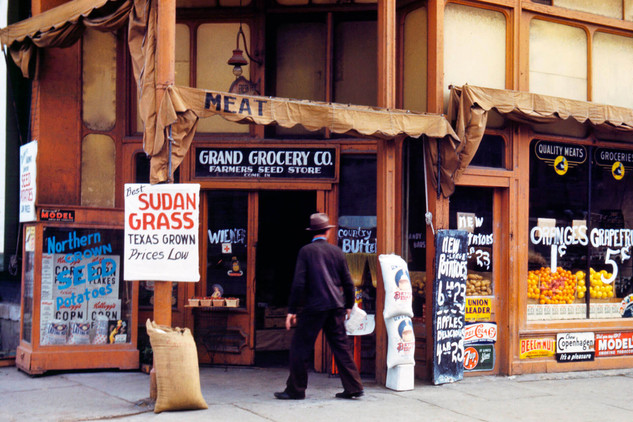

One of the landscapes in small-town America that Jack Kerouac crossed and described in his novel, On the road (1957).

Interview

Gaspard Koenig

Gaspard Koenig packed his bags for a five-month journey on horseback, from Bordeaux to Rome, in the footsteps of the ride undertaken by Montaigne in 1580, a journey that resulted in the publication of Notre vagabonde liberté (Our wandering freedom)1.

After becoming interested in Artificial Intelligence, the excesses of bureaucracy and standards, you made an about-face and decided to follow in the footsteps of a 16th-century philosopher… Why did you undertake such a trip?

My primary search is for freedom. And precisely, after having understood how algorithms and machine learning2 work, and having worried extensively about the phenomena of manipulation that this induces, I wanted to recover a certain kind of existential freedom. I wanted to take a trip that would insulate me from regulations and rules, and from normative environments. Going by horse was a good way to do it because when you are on horseback, nothing is provided for. One must constantly adapt, manage and make-do, all of which is really quite instructive. Montaigne was also a good guide, because he developed a philosophy of uncertainty, of chance, which is found in his way of writing, which is full of literary digressions, and in his way of travelling, which is equally full of detours of a more literal kind.

Was Montaigne’s travel journal, in its way, a guide?

It was a fellow traveller who off ered company, and with which I would not lose my temper! And it supplied a certain intimacy with Montaigne and his journey. I sometimes rediscovered very concrete situations that he describes in his book, such as when I was received in Florence by the Marquise Gondi, whose ancestor had welcomed the philosopher four centuries earlier, in the same palace and around glasses of the same wine. I was more surprised by the similarities with Montaigne’s account than by the diff erences. We believe that modernity reinvents everything, but the cities, the landscapes, and the people I met resembled Montaigne’s descriptions in many ways.

In the footsteps of Montaigne, Gaspard Koenig and his mare Destinada travelled 2,500km between Bordeaux and Rome.

A book and a horse. Isn’t that a way of travelling “with oneself” rather than travelling alone?

I was almost never alone. I crossed populated regions, I asked for hospitality, and the horse is certainly an animal that attracts interest and sympathy. People accompanied me sometimes, everyone spoke to me, in the evening I spoke to my hosts. I met many diff erent people, precisely because I set out alone on the journey. In a group, we tend to stick together and just focus inward. To meet others, sometimes you have to go it alone.

Does it give a particular meaning to the trip?

I find it extremely important for an intellectual to travel, to get out and experience the real world, to find and experience interactions between their ideas and reality. It is this confrontation with reality that gives true meaning to the journey. Montaigne considers that when the road is straight and you can see the goal in the distance, only boredom awaits. Truth is revealed when the route is winding and the destination is hidden. In a sense, you travel merely under a pretext of pulling at a thread. And a literary thread is even more pleasing, because it is such highly worked material...

1. Editions de l’Observatoire, 2021.

2. Artificial intelligence and computer science usigne data and algorithms to imitate the way that humans learn.

Gaspard’s five travel tips

1 - Build your own trip

Do not embark on a journey that many others have done before, but let yourself be guided by your own literary desires, building a journey around them instead. Avoid repeating paths that are too well known. One can simply choose to go to a place related to a book or a writer.

2 - Don't focus on just getting there

Avoid getting obsessed with the destination, the explicit reason for the trip. I almost didn’t achieve my goal of reaching Rome, because the horse was sick. I was disappointed at first, and then I finally figured it didn’t matter. This was just another twist, another hidden thread my trip was taking. We must learn to tell ourselves that if we take a detour, it doesn’t matter, we’ll just discover something else that’s new.

3 - Pack light

Take the book in electronic version, on a tablet! When travelling, it’s lighter, simpler and more practical on a daily basis. This was all the more important as on horseback one had to strip equipment down to a minimum.

4 - Make the experience fun

Find authors who have written a travel diary with fairly factual annotations, landscapes and descriptions, which will make the experience more fun, a bit like a treasure hunt. This requires rummaging around, as a historian would, comparing our modern situation to that of the story.

5 - Avoid marked routes

In the same way, it is better to avoid travel guides where everything is marked out, where each hostel is planned, one stage aft er another. Things then become somewhat superficial, with hospitality turning into mere commerce. True hospitality is when people trust you, welcoming you in a very generous, spontaneous way. These are the strongest most genuine of gestures.

Text

Olivier Cirendini

Journalist and freelance photographer specialising in tourism and travel,

Olivier Cirendini reports for the press and writes in many travel guides,

all while wondering about tourism, this most particular of human activities…