Mudam: a shining citadel of contemporary art

Built on the ruins of Fort Thüngen, an old fortress designed by Vauban, the museum of contemporary art is a blend of the new and the old with its enclosing walls and light Burgundy stones.

Can you tell us about how the Mudam came about?

The idea of setting up a museum of contemporary art in Luxembourg dates back to the 1980s, which was a period of great change. The Luxembourg government wanted to transform the country, which had once flourished through the steel industry, into a financial capital but also into a cultural hub. The original plans revolved around creating a modern art museum before eventually evolving into the concept of a contemporary art museum.

An extraordinary architect, Ieoh Ming Pei, was chosen to create this museum.

Indeed! Pei’s previous projects had fascinated the general public, who were very interested in the idea of creating a European “trilogy” of museums, consisting of the German Historical Museum in Berlin, the Louvre Pyramid in Paris, and the Mudam in Luxembourg. The history of this location played a fundamental role in Pei’s planning. The location of the museum on the Kirchberg is unique, as it literally stands on the ruins of the ancient fortress, Fort Thüngen. The volumes are thus simultaneously both modern and old, giving pride of place to both angles and curves. Light—also very important to Pei—floods the interior of the building through large panels and windows. It is also reflected by the light Burgundy stone walls. From the outside, the building looks like a fortress, but from inside it is an open, bright and very airy space.

How would you describe the museum’s collection?

Two parts make up our collection. We have numerous works by artists recognised across the international arts scene and in addition we have become the reference museum space for contemporary art created by Luxembourg artists, whose most important works we are ready to invest in. The collection brings together more than 750 pieces, and counting. We acquire new works every year, across all mediums, and more than 50 of these have also been commissioned because they resonate specifically with the space. The collection is truly a reflection of modernity and of questions being raised in the 21st century on issues such as identity, queer (or altersexual) culture, colonialism, and so on.

Do you collect digital art?

This is a question that is much discussed by most contemporary art museums these days. We have already put a significant emphasis on photography and cinema, and we feel it is important to make sure digital as well as virtual and augmented reality art is represented. Next year, we will be presenting works by Ho Tzu Nyen, a very technologically advanced Singaporean artist. Through such work, we are able to offer the public new narratives which are essential to meeting the expectations of younger generations.

The huge windows of the museum allow natural light to enter and highlight the exhibited works.

Beyond disseminating art, what are the responsibilities of museums towards the public and the communities of which they are a part?

The museum is considered a protected space in which people can come together and freely discuss any subject, at a time when society can be very polarised through social media. As a museum, we thus need to create a space where people can meet, gather and connect. Museums do indeed play an important role in the way stories are told, perceived and discussed. We are keen to keep up with trends that emerge over the short term, while maintaining sufficient distance from them to offer an overall perspective. We also need to connect with our social environment: one of the most important roles of art is to reflect society as a whole. Luxembourg is the home to large Italian and Portuguese communities and we want to take this more into account in our approach as a museum.

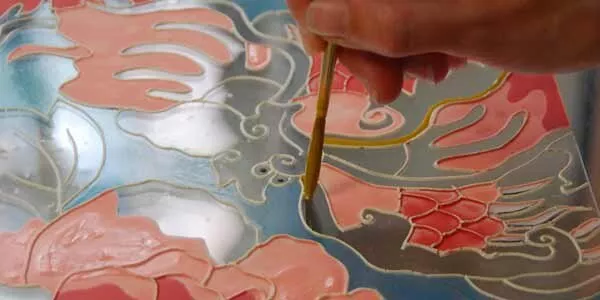

The museum offers contemporary paintings, such as that of Peter Halley, influenced by minimalism.

Is sustainability and the environment a subject that museums should also address?

Certainly! This is another big challenge we have to confront. This building was constructed in the late 1990s, when climate change was not really a priority. Glass is a material that is very present in its construction, which implies a significant need for heating during the cold season and for cooling during the summers, which are increasingly hot. We therefore need to explore new technologies that allow the glass to turn into solar panels or darken depending on sunlight levels. Beyond the building itself, we must ask ourselves about other subjects such as transport and travel: do we really need to transport works of art around the world and should we perhaps consider changing how our selection of work occurs, so we can operate more responsibly? To remain an international institution, which we want, we could consider, for example, inviting artists from Asia to work here and create works that would remain in the collection. This would significantly reduce the impact of transportation on the environment. Packaging materials could also be reused and/or made from recycled materials.

What about the exhibition programme and other news?

Currently we are exhibiting the great contemporary American painter Peter Halley (until October 15th), as well as Dayanita Singh (until September 10th), a major photographer and artist from India. Many public performance works will also be shown towards the end of the year. Digital art will be in the spotlight next year with an exhibition on the cyber-feminism of the 1960s and 1970s, as well as Agnieszka Kurant, a Polish artist who is very engaged in new technologies. And we also plan to offer meetings and festive gatherings in parallel with this programme!

Interview by Laurent Issaurat

Head of Art Banking Services, Societe Generale Private Banking.