Ceramics: an art on fire

Untitled ceramic by Kristin McKirdy, in enamelled ceramic, 2021.

For a decade, ceramics have been experiencing a new golden age. Beyond the interplay of fashions and infl uences, which regularly cycle back forms once thought forgotten, how do we explain its success in contemporary art?

In 2010, curator Nicolas Trembley exhibited his collection of German ceramic vases from the 1970s in Geneva. This collection, bought cheaply on eBay, had suddenly become newsworthy and was even described in Artforum magazine as “the very apotheosis of the meeting between high and low”. In 2016, the exhibition Ceramix drove the point home in Maastricht and Paris, with its wide selection of more than 250 pieces. And this trans historical art is now well established in the pantheon of contemporary art, as recently shown by the exhibitions Ettore Sottsass The Magic Object at the Pompidou Centre (with in particular, a series of monumental ceramic totems produced in 1969) and Flames at the Paris Museum of Modern Art, itself an ambitious show organised around the techniques, uses and messages of ceramics.

It’s a medium that not so long ago was thought of as old-fashioned, but has now become essential once more

A medium of experience

The term “ceramic”, is from the Greek keramos, meaning clay. This technique of shaping and fi ring clay fi rst appeared in the Neolithic period (6000-2500 BC approx.), serving multiple uses: making idols, various containers, even housing. This versatility still defi nes it, since ceramic is very much alive in the worlds of craft smanship, design and art. This craft smanship, has a long history and tradition around the world. On the design side, the Bauhaus school in Germany in the 1920s and Russian constructivism from the 1910s seized on ceramics as a way of transforming the material conditions of daily life. Today, ceramics is still heavily invested in by artists themselves, who remain faithful to it as a medium. While Elsa Sahal, Grayson Perry, Johan Creten or Natsuko Uchino work almost exclusively in ceramics, many artists try their hand at it upon invitation or at residencies. Thus, when Mimosa Echard created Purple Dose (2018), commissioned by a public maternity hospital in Geneva, she worked with the Swiss artist and ceramist Christian Gonzenbach and transposed the principle of production of her large wall paintings onto this medium. When Denis Savary began a collaboration with the Sicilian factory Ceramiche Fratantoni in 2017, it was the logical continuation of his sculpture pieces, that now involve ceramic artisans systematically. If ceramics now seem to be an obligatory “rite of passage” in the art world, it has also become a sculptural medium in its own right, as evidenced by the recent works of Rosemarie Trockel, Thomas Schütte or Ai Weiwei. However, it is rare for artists to embark on this adventure on their own: they are generally accompanied by collaborators in specialised workshops, following the example of Picasso’s iconic collaboration with the Madoura workshop in Vallauris.

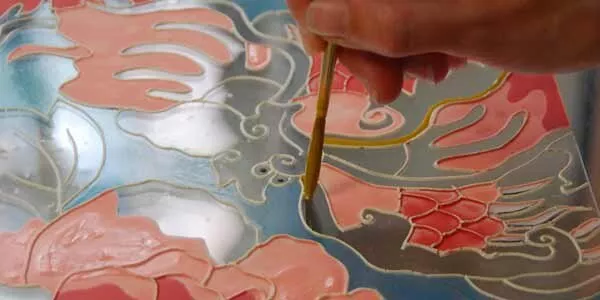

Ceramic by Emaux de Longwy. Capsule collection, summer 2021, conceived by Anthony Vaccarello, artistic director of the Saint Laurent house.

Oki by Ken Price Xavier Hufkens collection’s, Brussels (Belgium), 2007.

Chinzalée Sonami, creator of Pala ceramics, in his workshop in Oakland (United States).

A come-back?

Can we really talk about the return of ceramics as a go-to medium? The use of this material in sculpture dates from the modern era. Jean Carriès, Matisse or Rodin preceded Picasso and very early on developed “ceramic-sculpture” (the term is from Gauguin, who from 1886 worked in sandstone in the Parisian studio of Ernest Chaplet). The history of the avant-garde shows ceramics’ continued presence as a medium, from the Fauves (pictorial movement born in 1905) to the Surrealists (literary and artistic movement defi ned by André Breton in 1924) via the Futurists (European literary and artistic movement of the 1920s), who revisited everyday objects, such as in the works of Fortunato Depero or Giacomo Balla. From the 1930s, it was the proponents of informal art who experimented with the fi eld of ceramics. Lucio Fontana collaborated with the Mazzotti factory (which was already working with the Futurists), in Albisola, Italy. Far from the traditions of pottery, he developed an ambitious body of sculpture. In 1954, Karel Appel and Asger Jorn, from the Cobra group, settled in Albisola, a seaside resort on the Ligurian coast and worked with terracotta in all its forms, from the abstract to the fi gurative. The city remains a privileged location for those who are interested in this domain. The story continues in the 1950s and 1960s in California, where artists like Ken Price, Robert Arneson, Peter Voulkos, or his student Ron Nagle invented new uses for the material, with expressionist, pop or comic forms, which infl uenced entire generations. Then began a long eclipse where ceramics fell out of favour.

Ceramics reveal a specific concern of our times

This ended about ten years ago and since then the medium of ceramic has gone from strength to strength, even in the studios of art schools. Indeed, it allows for considerable experimentation in shape and enamelling, and is relatively easy to work with, even for those artists who are technical novices. Moreover, few artists have their own kiln and therefore tend to work in shared workshops, thus building a more collective environment of exchange. This success can also be interpreted as the reaction of the post-internet generation, articulating a refusal of the purely digital and a reaff irmation of the physical.

Sanders by Tony Cragg for the «Les Extatiques» exhibition on the parvis de La Défence in Paris (France), 2021.

A durable material

Finally, ceramic is a durable and therefore environmentally friendly material. For Vincent Pécoil, former gallery owner and current director of FRAC Normandie, the fashion for ceramics is thus “of a concern specific to our time, and participates in a predilection for forms and especially traditional materials perceived as a possible alternative to the modes of production which threaten our civilisation by causing all the upheavals that we know: climate change, depletion of resources, and environmental damage.” At an institutional level, in museums and other public art centres, interest in ceramics is part of a movement reassessing and revaluing minor arts and minority histories.

View of Elsa Sahal’s exhibition, Homage to Jambes Arp at the Galerie Papillon in Paris (France), 2021.

... An expanding market

Ceramics is no longer a niche market. For Thomas Bernard, gallery owner in Paris, it now enjoys very special attention, and the most important galleries defend this medium enthusiastically. Artists like Phyllida Barlow or Grayson Perry have caused prices to explode. We can also cite certain very small-format pieces such as those by Ron Nagle, which did not fi nd a buyer at auction in the 1990s, or at prices of around 3,000 euros, that are now selling, in galleries as well as in auction houses at around 50,000 euros per piece. At the same time, prices like those of Kristin McKirdy remain moderately valued: there are still pieces at auction for less than 5,000 euros. This is also the case for pieces by Martine Bedin and Nathalie Du Pasquier, of the Memphis group from the 1980s. Are there signs that the ceramics market, although expanding, remains more accessible than that of contemporary art? The fact remains that, as Thomas Bernard points out, the previous concern of collectors and institutions about the fragility of the medium and the problems of storage and circulation have generally subsided: “institutions currently perceive ceramics as an extraordinary medium. It is an ecosystem that is rehabilitating a medium perceived not so long ago as old-fashioned, and which has now become essential once more.”

Text

Jill Gasparina

Jill Gasparina was born in 1981.

She is a critic and freelance curator,

and teaches at the Geneva University of Art and Design (HEAD).